Introduction

Every time your friends ask you to tell them what you did during your vacation or what a movie was about, they are really asking for a summary. They want you to tell them the main events, but they’d be bored with every detail. The same skill is required to summarize what you read. You shorten the reading to the most important ideas and details. When you summarize, you show that you understand what you’ve read. Summarizing will help you remember what you read. When you write research papers, you will have to summarize your research before you can begin your analysis. This lesson will help you learn effective summarizing skills and techniques.

What’s in a Summary?

When you summarize, you reduce large sections of text to their essential points and main ideas. This means you must be able to identify main ideas and supporting points. Plus, you have to be able to remove all the less important details found in the original reading.

When you summarize you use your own words, but you do so without making any judgments or adding any opinions of your own.

Also, when you summarize, you must not forget to refer to the original source. In fact, the first line of your summary should state the title and the author of the original.

Summarizing Short Texts

Before you can begin to summarize, you must read the material several times for a full understanding.

With that in mind, read the following article. On your first reading make sure you understand all the words. Think about what the column is about. What is the columnist’s opinion? What is the main idea or message of the column?

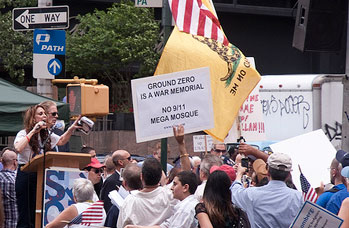

This op-ed from the New York Times was written in September 2010, when controversy arose over the building of an Islamic Cultural Center in Manhattan near Ground Zero, the site of the World Trade Center attacks in 2001.

America’s History of Fear

by Nicholas D. Kristof

September 4, 2010

A radio interviewer asked me the other day if I thought bigotry was the only reason why someone might oppose the Islamic center in Lower Manhattan. No, I don’t. Most of the opponents aren’t bigots but well-meaning worriers—and during earlier waves of intolerance in American history, it was just the same.

Screeds against Catholics from the 19th century sounded just like the invective today against the Not-at-Ground-Zero Mosque. The starting point isn’t hatred but fear: an alarm among patriots that newcomers don’t share their values, don’t believe in democracy, and may harm innocent Americans.

Followers of these movements against Irish, Germans, Italians, Chinese and other immigrants were mostly decent, well-meaning people trying to protect their country. But they were manipulated by demagogues playing upon their fears—the 19th- and 20th-century equivalents of Glenn Beck.

Most Americans stayed on the sidelines during these spasms of bigotry, and only a small number of hoodlums killed or tormented Catholics, Mormons or others. But the assaults were possible because so many middle-of-the-road Americans were ambivalent.

Suspicion of outsiders, of people who behave or worship differently, may be an ingrained element of the human condition, a survival instinct from our cave-man days. But we should also recognize that historically this distrust has led us to burn witches, intern Japanese-Americans, and turn away Jewish refugees from the Holocaust.

Perhaps the closest parallel to today’s hysteria about Islam is the 19th-century fear spread by the Know Nothing movement about “the Catholic menace.” One book warned that Catholicism was “the primary source” of all of America’s misfortunes, and there were whispering campaigns that presidents including Martin Van Buren and William McKinley were secretly working with the pope. Does that sound familiar?. . .

These kinds of stories inflamed a mob of patriots in 1834 to attack an Ursuline convent outside Boston and burn it down.

Similar suspicions have targeted just about every other kind of immigrant. During World War I, rumors spread that German-Americans were poisoning food, and Theodore Roosevelt warned that “Germanized socialists” were “more mischievous than bubonic plague.”

Anti-Semitic screeds regularly warned that Jews were plotting to destroy the United States in one way or another. A 1940 survey found that 17 percent of Americans considered Jews to be a “menace to America.”

Chinese in America were denounced, persecuted and lynched, while the head of a United States government commission publicly urged in 1945 “the extermination of the Japanese in toto.” Most shamefully, anti-Asian racism led to the internment of 110,000 Japanese-Americans during World War II.

All that is part of America’s heritage, and typically as each group has assimilated, it has participated in the torment of newer arrivals . . .

But we have a more glorious tradition intertwined in American history as well, one of tolerance, amity and religious freedom. Each time, this has ultimately prevailed over the Know Nothing impulse.

Americans have called on moderates in Muslim countries to speak out against extremists, to stand up for the tolerance they say they believe in. We should all have the guts do the same at home.

Now answer the questions below using your Take Notes Tool. Keep the Take Notes Tool open in order to retain your work for subsequent exercises in this lesson. Check your understanding when you are finished.

- In one word, what is this column about?

- Is Kristof for or against the building of the Islamic Cultural Center? How do you know?

- What is Kristof’s message, or main idea?

- Possible answers: fear, intolerance, bigotry.

- He doesn't take a formal stance, but he believes that those who are against it are misinformed.

- Americans have always been afraid of newcomers and new ideas, but we should follow our own beliefs and be more tolerant.

Now you have a general idea of what the article is about, the author’s opinion, and the main idea. All three are very important for writing a summary. However, your summary must also include the most important supporting details.

Read the column again. This time, you’ll be taking some brief notes on the article, using a graphic organizer. Your notes should not be full sentences; use as few words as possible to help you remember. Look up any historical references you don’t understand. The graphic organizer will give you space to record your comments and responses. You can save, download, or print the graphic organizer.

Here’s the same graphic organizer that shows how one person might have used it to make notes.

Now that you’ve read the column twice, you are ready to begin your summary. Look back at your notes in your graphic organizer. Your notes should provide enough information to write a summary. What’s great about using only your notes is that you have less material to worry about and won’t get hung up on details.

As you begin your summary, follow these handy directions:

- State the title and credit the author of the original reading.

- Cover the main ideas and essential points from the original reading.

- Reduce the original; your summary should be shorter.

- Write enough to convey the main ideas and supporting ideas.

- Leave out your own ideas, opinions, and judgments.

- Use your own words rather than those of the original writer.

Use your Take Notes Tool to write a draft of a summary. Keep your Take Notes Tool open for the additional instructions that follow.

Now revise your summary if it’s missing any of the necessary elements listed below. Check off the elements below as you add each one to your summary.

A good summary will:

- State the title and credit the author of the original reading.

- Cover the main ideas and essential points from the original.

- Be shorter than the original.

- Be long enough to give a good sense of the main ideas and supporting ideas.

- Leave out your own ideas, opinions, and judgments.

- Use your own words rather than those of the original writer.

Ok, now that you’ve read back through your summary and revised it, go back to the column and read it a third time.

Does the article contain any important information that you forgot to mention? If so, add that to your summary.

Did you include any information in your summary that really isn’t very important? If so, remove it.

Now, here’s the kicker: if your summary is longer than two paragraphs, shorten it. Just make sure you don't lose the columnist’s main idea or most important points. Use your Take Notes Tool to shorten your summary. When you’re finished, check your understanding.

In “America’s History of Fear,” columnist Nicholas Kristof responds to the recent controversy surrounding the Islamic Cultural Center in Manhattan. He explains that Americans have a long history of intolerance toward those who are different. The fears that cause the intolerance are inflated by demagogues who exaggerate differences.

CloseSummarizing Long Texts

You’ve learned a strategy for summarizing an article or another short text. But how does this transfer to a longer text, such as an entire book?

You can use the same strategy. Beginning with the first chapter, make notes in the margins. Use sticky notes if the book is not your own. As you finish each chapter, use your notes to write a summary until you have one for each chapter in the book. When you finish, use only your chapter summaries to write your book summary.

Another strategy some readers use when reading books or plays is to keep a running outline. They write on the book’s inside flap or on a large sticky note attached to the inside front cover.

With this strategy, add to the outline as you read each chapter, act, or scene. When you’ve finished the book or play, you will have an outline of the entire work. You can use the outline to write a summary.

If you use this strategy, remember that fiction is not always written chronologically. Flashbacks are common, and authors often write each chapter from a different character’s point of view. So, when you write your summary, you may have to adjust your ideas so your summary tells events chronologically.

Let’s look at an outline a reader made as he read Shakespeare’s play Romeo and Juliet. If you’ve read the play or seen the movie, you can probably write a summary from the reader’s outline. If not, you might want to read the play at this Shakespeare site from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Romeo and Juliet

by William Shakespeare

Painting of William Shakespeare

Painting of William Shakespeare Act I

Prologue: Short summary given. Two families in Verona. Old enemies. Their children fall in love.

Scene 1: Fight breaks out between Capulets and Montagues. The Prince warns that the families will pay with their lives if battle breaks out again. Romeo is lovesick.

Scene 2: Capulets want Paris to marry Juliet. They set up a party for Paris and Juliet to meet. Benvolio encourages Romeo to go to the Capulet party.

Scene 3: Lady Capulet talks with Juliet about getting married. Juliet is not happy about the idea of marrying Paris.

Scene 4: Romeo and friend Benvolio prepare to crash the party.

Scene 5: Romeo notices Juliet at the party. Tybalt (Juliet’s cousin) notices Romeo and tells Lord Capulet. Lord Capulet refuses to throw Romeo out. Romeo flirts with Juliet. Romeo finds out Juliet is a Capulet. Romeo and Benvolio leave the party. Juliet finds out Romeo is a Montague.

Act II

Prologue: Summary given of Romeo’s situation. He’s now in love with Juliet but has no access to her.

Scene 1: Benvolio and Mercutio (another friend) joke about how Romeo has fallen in love again.

Scene 2: Juliet speaks her love for Romeo out the window of her room. Romeo, hidden in the Capulet orchard, hears Juliet and confesses his love for her. They agree to meet.

Scene 3: Romeo discusses his new love for Juliet with Friar Laurence.

Scene 4: Romeo and friends are joking around. Juliet’s nurse comes to plan a meeting where Romeo and Juliet can get together.

Scene 5: The nurse tells Juliet to meet Romeo at the friar’s.

Scene 6: Romeo and Juliet get married.

Representing the famous balcony scene

Representing the famous balcony scenefrom Romeo and Juliet. 1884 painting

by Frank Dicksee.

Act III

Scene 1: Tybalt comes to quarrel with Romeo, but Romeo refuses to fight. Tybalt kills Mercutio. Romeo gets revenge by killing Tybalt.

Scene 2: Juliet learns that Romeo killed her cousin.

Scene 3: Romeo is banished.

Scene 4: Lord Capulet plans for Juliet to marry Paris on Thursday.

Scene 5: Romeo tells Juliet he must leave. Lady Capulet tells Juliet that she is to marry Paris. Juliet argues with her parents.

Act IV

Scene 1: Paris tells Friar Laurence that he and Juliet are to be married. Juliet tells the friar that she wants to commit suicide. Friar Laurence gives Juliet a potion that will put her to sleep so her parents will think she is dead. He will send a message to Romeo to come for her.

Scene 2: Juliet returns home and tells her parents she will marry Paris.

Scene 3: Juliet and the nurse prepare for the wedding. Later Juliet takes the potion.

Scene 4: The Capulets prepare for the wedding.

Scene 5: Capulets find Juliet “dead.”

Act V

Scene 1: Romeo learns that Juliet is dead and decides to kill himself.

Scene 2: Friar Laurence learns that his letter to Romeo was never delivered.

Scene 3: Romeo goes to find Juliet’s body, presumably dead. Paris stops Romeo at the tomb. Romeo kills Paris. Romeo takes poison and dies. The friar finds Romeo’s and Paris’s bodies. Juliet wakes up and will not go away with the friar. She sees Romeo’s body. She tries to kill herself with Romeo’s poison, but instead stabs herself with his dagger. Families learn of the deaths and make peace.

Now look over this outline, and write a summary of the play. Download the outline as an editable document to help you take notes on individual acts. Use the notes to build your summary like we did with Kristof’s newspaper column. Write your summary using theTake Notes Tool.

Again, remember the elements of a summary, and apply them to the book or play summary as well. The summary should not include your own ideas, opinions, or judgments.

A good summary of the original text, however, should include the following:

- The title and name of the author.

- A shorter version of the original text.

- The main ideas and supporting ideas.

- Your own words rather than those of the original writer.

Go ahead and edit your summary if you have forgotten any of these components. Copy and paste your new summary into the space below to see if it’s short enough. If your summary doesn’t fit, cut out unimportant details to make it fit. When you’re finished, check your understanding to see another possible summary of the text.

William Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet is a tragic story of love, death, and poor timing. The play begins with a battle between the Capulet and the Montague families. Following the battle, the prince threatens death to anyone from the feuding families who starts another battle. The Capulets, hoping to marry their daughter Juliet to the noble Paris, put on a party so the two will meet. Romeo, the son of the Montagues crashes the party. Instead of falling for Paris, Juliet meets Romeo, and the two fall in love.

Hiding in the orchard below Juliet’s house, Romeo overhears Juliet confess her love for Romeo. He responds with similar sentiments, and soon the two are secretly married. Unfortunately, Juliet’s cousin Tybalt ignites a fight with Romeo for crashing the party and kills Romeo’s best friend. Enraged, Romeo takes revenge and kills Tybalt. Having broken the law, Romeo is banished. While Romeo is away, Juliet’s parents engage her to Paris and begin wedding plans. To help Juliet with her predicament the friar gives Juliet a potion that will put her into a death-like sleep. The friar sends a note to Romeo to let him know the plan, but the note never reaches Romeo. Instead, everyone believes Juliet is dead, and word of her death reaches Romeo. He returns to find her "dead," and takes poison to kill himself. When Juliet wakes to see Romeo dead, she stabs herself.

CloseYour Turn

Now use the strategy you learned for the article to write a very brief summary of the historical document that follows by doing these steps:

- Read once to get the main ideas and to be sure you understand all the words.

- Read again, annotating the text in the margin.

- Draft your summary, looking only to your notes.

- Read the original document again to be sure you didn’t leave out anything important.

- Check your summary against these rules:

- State the title and credit the author.

- Cover main ideas and essential points.

- Keep it short, but write enough to give a good sense of the main ideas and supporting ideas.

- Don’t include your own ideas, opinions, or judgments.

- Use your own words.

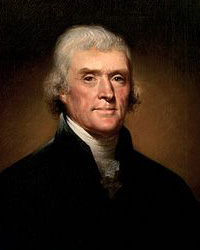

Portrait of Thomas Jefferson by Rembrandt Peale in 1800.

Portrait of Thomas Jefferson by Rembrandt Peale in 1800. from The Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom

by Thomas Jefferson

I. Whereas Almighty God hath created the mind free; that all attempts to influence it by temporal punishment or burthens, or by civil incapacitations, tend only to beget habits of hypocrisy and meanness, and are a departure from the plan of the Holy author of our religion, who being Lord both of body and mind, yet chose not to propagate it by coercions on either, as was his Almighty power to do . . .

II. Be it enacted by the General Assembly, that no man shall be compelled to frequent or support any religious worship, place, or ministry whatsoever, nor shall be enforced, restrained, molested, or burthened in his body or goods, nor shall otherwise suffer on account of his religious opinions or belief; but that all men shall be free to profess, and by argument to maintain, their opinion in matters of religion, and that the same shall in no way diminish, enlarge, or affect their civil capacities.

III. And though we well know that this assembly elected by the people for the ordinary purposes of legislation only, have no power to restrain the act of succeeding assemblies, constituted with powers equal to our own, and that therefore to declare this act to be irrevocable would be of no effect in law; yet we are free to declare, and do declare, that the rights hereby asserted are of the natural rights of mankind, and that if any act shall be hereafter passed to repeal the present, or to narrow its operation, such as would be an infringement of natural right.

After you have finished drafting and revising your summary, copy and paste your final summary here to see if it is short enough. When you're finished, check your understanding to see another possible summary of Jefferson's text.

Thomas Jefferson writes in an excerpt from “The Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom” that God has created all of us with a free mind, so the state should not dictate a person’s religious beliefs. He also says that a person should be able to perform civic responsibilities regardless of religious beliefs.

He concludes by saying that he can’t know what bodies of government will do in the future, but because the right to worship as we choose is a natural right, he thinks that governments in the future will agree with this statute too.

CloseTest Your Understanding

Complete the following steps to take a quiz that tests your understanding of this topic.

- Click on the link below. The quiz will open in a new window.

- When you have completed the quiz, click the Submit button.

- Close the window to return to this page.

- To review your test results, click the Tests/Quizzes button in the left-hand Epsilen navigation menu to open the Tests/Quizzes page.

- Under Past Tests/Quizzes locate the test for Reading: Module 1: Lesson 7 and click on the magnifying glass icon to view your results.

Please Note: Question/answer choices periodically appear out of order onscreen. This is a known program bug within Epsilen and is currently being addressed.

Resources Section

Resources Used in This Lesson: Bibliography

Jefferson, Thomas. Virginia’s Statute on Religious Freedom. Virginia Historical Society. 1786. http://www.vahistorical.org/sva2003/vsrf.htm.

Kristof, Nicolas D. “America’s History of Fear.” New York Times. September 4, 2010. http://www.nytimes.com/

2010/09/05/opinion/05kristof.html?ref=nicholasdkristof.

Shakespeare, William. Romeo and Juliet. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. http://shakespeare.mit.edu/

romeo_juliet/full.html.