Introduction

We have all been using appeals practically since birth. As infants, we learn that crying or cooing brings us the results we desire. As toddlers, we might try throwing temper tantrums to get our way, but usually our parents choose to ignore them, and we have to find a more reasonable approach. By the time we become teenagers, we've had endless practice trying to get our way with the adults (and others) in our lives.

Aristotle identified the three main appeals—ethical, logical, and emotional—and you have been using them in your efforts, maybe unknowingly. But you've grown well aware of what methods work best with each audience, and you probably have had increasingly successful results. You have had to learn to apply different appeals to different audiences and different circumstances, and you likely have used all three in your strongest arguments because, in a good argument, the three appeals are closely intertwined.

Some people react strongly to appeals to their “head” or through reason—the appeal to logic. Others react more to appeals to their “heart” or through “feelings” —the appeal to emotion. All people respond best if they perceive the arguer is “trustworthy” through appeals to their “gut” (instinct) or their “hand” (partnership)—the ethical appeal.

Through this lesson you will recognize how writers design their arguments to win us over just as you have been doing with the people you know, and you will acquire a greater understanding not only of other people, but also of your own values, beliefs, tastes, desires, and feelings.

Identifying the Appeals

Understanding How the Appeals Work

View this presentation about how the appeals (emotional, logical, and ethical) work, the body parts to which they refer, and how the appeals are incorporated into argument.

You will now use interactive worksheets to analyze dominant appeals in three passages. The chart below explains what how to use the worksheets.

|

Dominant Appeal

|

Supporting Quotation(s) for Each

|

Explanation of Effect(s)

|

|---|---|---|

| First, state which of two appeals is strongest in the passage—logical or emotional. (An arguer always tries to be “ethical” in a strong argument, so here choose between the other two appeals.) | Next, include important wording and figures from the passage. You may quote just single words or phrases if diction or imagery helps create the appeal. Two to three examples are sufficient. | Finally, describe what the passage is doing and how. |

Below is an example using sentence #10 from the exercise in the section "Understanding How the Appeals Work."

And the dispossessed, the migrants, flowed into California, two hundred and fifty thousand, and three hundred thousand. Behind them the new tractors were going on the land and the tenants were being forced off. And new waves were on the way, new waves of the dispossessed and the homeless, hardened, intent, and dangerous. (The Grapes of Wrath, 318)

|

Dominant Appeal—Logical or Emotional?

|

Supporting Quotation(s)

|

Explanation of Effect(s)

|

|---|---|---|

|

Emotional |

“two hundred and fifty thousand” |

The author uses increasingly large numbers and the words “new waves” twice to emphasize how many people were affected by the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression. His diction captures the essence of the emotions people experienced when pushed off their lands by forces beyond their control. |

Remember: the ethical appeal, which is the persuasive value of the writer’s character, must be established through the text alone. When writers create arguments—as they generate, organize, and express their ideas—they aim to make the audience believe they have good sense, good will, and moral integrity.

Now that you see what to do, practice finding the appeals and working with them in three passages from literature. Click here to access the worksheets. You type into them on the screen and/or download and print them. When you are finished reading and filling out the worksheets, follow the directions provided on each page to compare your responses.

Analyzing Appeals in Advertisements

Advertisements offer effective examples that show how language and visuals can manipulate us and may be the most pervasive “arguments” in our culture. As you analyze the appeals in the advertisements below, consider the power of the advertising industry as described in the online article “Madison Avenue Continues as Advertising’s Economic Center”. Click on the numbers in the article as you read.

As of October 14, 2010, . . . advertising expenditures overall account for $5.8 trillion of the $29.6 trillion in total U.S. economic output, nearly 20 percent of the country’s economic activity . . . The ad expenditures support 19.8 million of the nation’s 133.4 million jobs, about 15 percent . . . Each million dollars of ad spending results in the creation of 69 American jobs.

These staggering numbers explain why everyone in our society is constantly confronted by ads.

Another article discusses the effects of advertising on students:

![An 1890s advertising poster shows a woman in fancy clothes (vaguely influenced by 16th- and 17th-century styles) drinking Coke. The card on the table says "Home Office, The Coca-Cola Co. Atlanta, Ga. Branches: Chicago, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, Dallas". There are cross-shaped color registration marks near the bottom-center and top-center (which presumably would have been removed for a production print run). Someone has crudely written on it at lower left (with a fountain pen that was apparently leaking), "Our Favorite" [sic].](http://ontrack-media.net/english3/images/E3RdM2L05img2.jpg)

Unless students understand how to read and analyze the language of the symbols and images bombarding them, their identities will be shaped unconsciously. And because advertising’s portraits reflect essentially insecure identities, the images promoted point the way to more, rather than less, emotional emptiness. Advertising’s images of human relationships and sexuality make playing the game of measuring up to Madison Avenue downright crippling. (Moog, Carol, “Ad Images and the Stunting of Sexuality,” 1994)

The close examination of ads can make us conscious of their purpose and whether or not they work on us. (Note: Generally, the more text there is, the greater the appeal to logic. The less text there is, the greater the appeal to emotion.)

Advertisement #1: “Marge Simpson for Dove Hair Care”

First, analyze the image and the text of the ad. You do not need to write these answers down.

- Describe Marge’s appearance before she uses “Dove Anti-Frizz Cream” on her hair.

- Describe her appearance after she uses the product.

- Which image is more appealing? Why?

- Now examine the text of the ad. Notice the sentences in the largest font; what does Dove promise?

- What does the first sentence in smaller font promise? To whom is Dove appealing when it uses “foxy mamma” to describe hair after using the product?

- What three results can a user expect from promises in the second sentence?

- What does “Welcome to blue heaven” mean?

- What does the slogan “unstick your style” mean?

- Where can a potential buyer find the product?

- Finally, in the upper right corner, Dove gives a website for this particular ad campaign. What is the company focusing on?

Next, draw inferences from the ad.

- Why is Marge a good choice for a hair-care product?

She's a recognized cultural icon.

Close - Who is the intended audience?

Young or young-at-heart females who watch television and who want to look nicer.

Close - What effect do you think the ad has on this audience? Why?

Amusement. Marge's regular hair looks funny; the use of the product makes it look better

Close - Is the major appeal to logic or to emotion? Explain.

Emotion. The strategy of making Marge look better appeals to our need to look better and more attractive.

Close - What is the unstated promise of the ad?

Use this hair-care product and you'll be attractive and sexy.

Close - Is there a fallacy or fallacies? Explain.

Yes. It's a non sequitur—it does not follow that if you use this hair-care product that you will be prettier and sexier.

Close

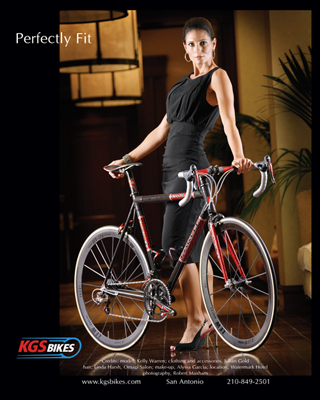

Advertisement #2

First, analyze the image and the text of the ad. You do not need to write the answers down.

- Describe the photo. How is the gecko different from how you see him in the television commercials?

- How much text is there in relation to the previous ad?

- What is humorous in the large font next to the gecko?

- What are some of the main points of the paragraph in smaller font?

- How does the ad circle back to the beginning?

Second, draw inferences from the ad.

- Why did the ad creators choose the image of the gecko?

It's a recognized cultural icon.

Close - Why did they change his appearance?

To look more intelligent, even professorial.

Close - Who is the intended audience?

People who need to purchase car insurance.

Close - What effect do you think the ad has on this audience? Why?

Amusement. Because having a lizard say anything at all is funny, and to make it "intelligent” is even more so.

Close - Based on the amount of text in the ad, is the major appeal to logic or to emotion?

Logic.

Close - Where is there a blatant appeal?

Save hundreds of dollars—appeal to the pocketbook.

Close - Is there a fallacy or fallacies? Explain.

Yes. Non sequitur—it does not follow that, just because Geico is associated with Warren Buffet, the company will sell you a money-saving policy.

Close

Advertisement #3

First, watch the video of the commercial closely. Then watch it once more, and consider these questions about the content:

- Describe the person in the commercial.

- Describe the setting.

- Describe what happens.

- How much of the ad is verbal?

Next, draw inferences from the commercial.

- What is the purpose of the commercial?

To sell the Toyota Vios.

Close - Who is the audience?

Young car buyers.

Close - What makes the ad effective?

The surprising ending with an aquatic monster grabbing the jogger and setting the car back up as a trap for the next curious person—lunch!

Close - Explain what the major appeal is in the ad.

It's emotional because there's no dialogue. There are just a few words at the end of the commercial—and the monster's use of the car as a lure is a delightful twist. We don't expect it.

Close - Is there a fallacy or fallacies? Explain.

Yes. Aquatic monsters are myths. Even if they did exist, they wouldn't use cars this way. The advertisers probably know that a viewer of this commercial would not buy the car based on what happens. But the viewer will definitely remember it!

Close

If you wish to gain an understanding of what goes into an advertising sales campaign, watch this clip from the award-winning television show Mad Men, a drama about the advertising industry set in the 1960s. Critics have praised the show's visual style and historical accuracy. Therefore, as you watch, you need to keep in mind that people used to smoke in the workplace—in this clip, they are smoking heavily. First, watch the entire clip without stopping. Then watch it again.

Another clip from Mad Men (“Who Cares?”) shows how some employees in the advertising industry lack ethics.

And finally, this clip from Mad Men (“Lucky Strike Ad Pitch”) gives some idea of how far advertisers will go to sell a product, even a product known to cause cancer and premature death.

Resources

Resources Used in this Lesson: Bibliography

The Ad Show. “Dove-Marge Simpson.” (accessed November 27, 2010).

Ehrenreich, Barbara. Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America. New York: Henry Holt and Co., 2001.

Elliot, Stuart. 2009. “Geico’s Lizard Offers a New Message of Reassurance.” New York Times, February 18.

Moog, Carol, “Ad Images and the Stunting of Sexuality.” Images in Language, Media, and Mind. Ed. Roy F. Fox. (Urbana, IL: NCTE, 1994).

Pitts, Leonard. “We Need a History Lesson About Nazis.” Austin American-Statesman. August 20, 2009.

Schlosser, Eric. Fast Food Nation: The Dark Side of the All-American Meal. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 2001.

Shepard, Adam. Scratch Beginnings: Me, $25, and the Search for the American Dream. Chapel Hill, NC: SB Press, 2008.

Steinbeck, John. The Grapes of Wrath. New York: Viking Press, 1939.

“Toyota Loch Ness.” YouTube video, 00:31. Posted February 17, 2007.

“Mad men one of the best scene 'who cares ?' S01 E12.” YouTube video, 2:51. Posted 29, 2009.

“Madmen Lucky Strike Ad Pitch.” YouTube video, 2:39. Posted November 4, 2009.