Introduction

Imagine this scenario: Mona wrote and turned in what she considered to be a well-written essay. She was so interested in the topic and had so much to say about it that she hadn’t even minded doing the assignment. Her essay had an interesting introduction, detailed body paragraphs, and a satisfying conclusion. The spelling, verb usage, and pronoun references were correct. All in all, Mona felt confident that the paper deserved a high grade. She wasn’t prepared for the mediocre score it received or for the brief note of explanation: “Numerous sentence structure errors.”

Mona had failed to check individual sentences to ensure that each of them was complete. The fragments and run-ons in her essay not only impacted her grade, but they also made Mona’s writing skills seem questionable. This lesson will give you tools and tips to edit sentence structure, so that you can escape Mona’s fate and guarantee that fragments and run-ons won’t hamper your writing.

Understanding Phrases and Clauses

Before you can edit for sentence structure, you must understand the difference between phrases and clauses, and you must know how these groups of words operate within sentences. If you don’t grasp phrases and clauses, you will only be guessing about sentence structure, not editing for it based on understanding. While this section doesn’t deal with everything there is to know about phrases and clauses, it does cover the major points you need to know to check for proper sentence structure.

Phrases

Know the definition of a phrase, and be aware that there are several kinds. You don’t have to memorize the types, but you do need to recognize how they function in sentences. In most cases, a phrase acts as a single part of speech. What follows is a brief review of the types of phrases used most often.

Prepositional phrase: Begins with a preposition and usually ends with a noun or pronoun; acts as an adjective, adverb, or occasionally a noun

- After the movie will be too late. (acts as a noun )

- The package on the porch is mine. (acts as an adjective that modifies package)

- Jasper ran from Grace and me. (acts as an adverb that modifies ran)

Participial phrase: Contains a participle and its modifiers; acts as an adjective

- The girl, walking too rapidly, tripped on the curb. (acts as an adjective that modifies girl)

- Destroyed by flood waters, the home was never rebuilt. (acts as an adjective that modifies home)

Gerund phrase: Contains a gerund and its modifiers; acts as a noun

- Telling the secret was a big mistake. (acts as a subject)

- My counselor advised sending college applications early. (acts as a direct object)

Infinitive phrase: Contains an infinitive (to plus the root of the verb) and its modifiers; acts as a noun, adjective, or adverb

- To save money is one of my goals. (acts as a noun subject)

- There must be a way to solve this problem. (acts as an adjective that modifies way)

- Jorge went to college to study physics. (acts as an adverb that modifies went by telling why)

Noun phrase: Contains a noun and any associated modifiers; acts as a noun

- The long and curvy driveway leads up to my house. (noun driveway and its modifiers; acts as a subject)

- An arsonist burned the old building by the railroad tracks. (noun building and its modifiers, which include the prepositional phrase by the railroad tracks; acts as a direct object)

Appositive phrase: A noun phrase that follows another noun or pronoun to explain or identify it

- Her car, a beautiful red Corvette convertible, cost more than I’ll earn working all year. (noun phrase that identifies car)

- His biggest regret, an argument he caused, would haunt him for the rest of his life. (noun phrase that explains regret)

- Marco’s dream, his desire to become a professional basketball player, was the reason he pushed himself so hard at every practice. (noun phrase that explains dream)

Look back at the phrases in red. They are located in different places in the sentences and function in different ways, but they do have one thing in common: they can never be complete sentences by themselves. Check your essays carefully, and if you find that you’ve used a phrase as a sentence, either eliminate it, or fix it by adding the elements it’s missing to make a complete sentence.

Clauses

In terms of sentence structure, clauses are even more important than phrases because clauses are the main building blocks of sentences. Unlike phrases, all clauses have both a subject and a verb. You must, however, be able to differentiate between the two major categories of clauses. Understanding clauses will help you avoid the two big sentence structure errors we’ll look at later.

As we look carefully at clauses, keep in mind this guiding principle of editing for sentence structure: a complete sentence must include at least a subject and a verb in one independent clause.

Independent clause: Also called a main clause, this type of clause can stand by itself as a complete sentence. Independent clauses are strong, just like independent people are strong and can get along by themselves.

- Zeke broke the expensive vase. (independent clause; Zeke is the subject, and broke is the verb)

- Zeke broke the expensive vase when he was six years old. (independent clause; can be removed from the sentence and stand alone.)

It’s not too difficult to recognize and use independent clauses correctly, is it? Unfortunately, the same cannot be said of the second category of clauses.

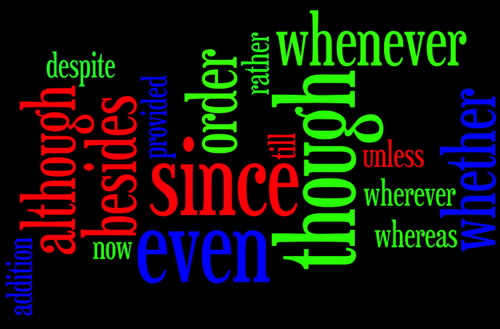

Subordinate clause: Also called a dependent clause, this type of clause can cause problems because it cannot stand by itself as a complete sentence. Subordinate—or dependent—clauses are just like dependent people. They are not strong enough to get along by themselves; they need help to become sentences. In fact, the word subordinate means “controlled by another.” The good news is that this kind of clause is easy to spot. A dependent clause will begin with either a subordinating conjunction or a relative pronoun. A list of subordinating conjunctions appears in the graphic below.

- Zeke broke the vase when he was six years old. (subordinate clause; begins with the subordinating conjunction when; the subject of the clause is he, and was is the verb)

- When he was six years old. (Yikes! This subordinate clause cannot stand as a complete sentence.

There are three kinds of subordinate clauses. Each kind acts as a single part of speech—an adjective, adverb, or noun—within a sentence.

Adjective clause: a subordinate clause that modifies a noun or pronoun

- The house where Shakespeare was born is still standing. (adjective clause; begins with subordinating conjunction where and modifies the noun house)

- She was one who complained every day. (adjective clause; begins with relative pronoun who and modifies the pronoun one)

Adverb clause: a subordinate clause that modifies a verb, adjective, or another adverb

- Ruth watches television whenever she can. (adverb clause; begins with subordinating conjunction whenever and modifies the verb watches)

- Taylor feels confident that he will win the contest. (adverb clause; begins with subordinating conjunction that and modifies the adjective confident)

- Sally sings better than I do. (adverb clause; begins with subordinating conjunction than and modifies the adverb better)

Noun clause: a subordinate clause used as a noun within an independent clause

Note: Because noun clauses substitute for nouns within independent clauses instead of modifying other words, they can be more difficult to spot than adjectives or adverb clauses.

- The newspaper editor knows why the reporter is in trouble. (noun clause; acts as a direct object within the independent clause)

- Whether the plan will work remains a mystery. (noun clause; acts as a subject within the independent clause)

- Josh’s teachers are concerned about what his semester grades will be. (noun clause; acts as the object of the preposition about within the independent clause)

Now that you’ve reviewed phrases and clauses, it’s time to see how well you understand the differences between them. Choose “independent” or “subordinate” for each of the following phrases and clauses.

Remember that independent clauses include a subject and a verb and can stand alone as a complete sentence; subordinate clauses cannot stand alone, and they begin with a begin with a subordinating conjunction or a relative pronoun.

Now let’s throw phrases into the mix. See if you can pick phrases, independent clauses, and subordinate clauses out of sentences.

Think about whether the words blue in each sentence are a phrase, an independent clause, or a subordinate clause. When you have an answer in mind, roll over the blue part of the sentence to see the correct response.

Recognizing and Editing for Fragments

Even Uncle Sam wants your sentence structure to be correct.

Even Uncle Sam wants your sentence structure to be correct. Armed with knowledge about phrases and clauses, you are ready to edit for sentence structure. Let’s start by looking at fragments, an error that results in lower grades and causes teachers and bosses to pull out their hair.

Sentence structure problem #1: Fragments

So what exactly is a fragment? The word itself tells you that it’s a piece of something; in this case, it is a piece of a sentence. A fragment is an incomplete sentence because (1) it lacks a subject, or (2) it lacks a verb or part of a verb, or (3) it is a subordinate clause. A fragment is a phrase or a subordinate clause pretending to be a sentence.

Now that you’re sure what sentence fragments are, let’s consider how to fix them. The simplest fixes involve zeroing in on what is missing.

If a fragment is missing a subject, add a subject.

- Fragment: Figured out that she was going to be in trouble

- Corrected sentence: Theresa figured out that she was going to be in trouble.

If a fragment is missing a verb or part of the verb phrase, add it.

- Fragment: Children playing in the park

- Corrected sentence: Children were playing in the park.

If a fragment is a subordinate clause, attach it to a nearby independent clause. That independent clause could be the sentence before or after the subordinate clause—or you could add a new independent clause to make the sentence complete.

- Fragment: Although she doesn’t want to admit it

- Corrected sentence: Mom likes rock music, although she doesn’t want to admit it. (Alternative: Although she doesn’t want to admit it, Mom likes rock music.)

If a fragment is a prepositional phrase, add whatever it needs to make it a complete sentence.

- Fragment: On the bedroom floor

- Corrected sentence: Jerry’s clothes were on the bedroom floor.

(Alternative: On the bedroom floor was the biggest cockroach I had ever seen.)

To check your understanding of fragments, do the brief interactive exercise.

Recognizing and Editing for Run-ons

Sentence structure problem #2: Run-on sentences

Run-on sentences are probably even more prevalent than fragments. Run-ons raise the anxiety level of students who don’t know how to fix them. They agitate teachers who keep seeing them in essays. They bother bosses who expect their employees to use proper sentence structure in workplace writing.

The term “run-on” is a perfect name for these would-be sentences. A run-on is actually two independent clauses that have been improperly run together. The clauses need to be separated into two sentences or joined into one. Comma splice is the name for a specific kind of run-on in which a comma improperly joins two independent clauses.

NOTE: People sometimes think that if a sentence is long, it must be a run-on, but that is not true. Take, for example, the following sentence from Phillip Roth’s 2004 novel A Plot Against America:

Elizabeth, New Jersey, when my mother was being raised there in a flat over her father’s grocery store, was an industrial port a quarter the size of Newark, dominated by the Irish working class and their politicians and the tightly knit parish life that revolved around the town’s many churches, and though I never heard her complain of having been pointedly ill-treated in Elizabeth as a girl, it was not until she married and moved to Newark’s new Jewish neighborhood that she discovered the confidence that led her to become first a PTA “grade mother,” then a PTA vice president in charge of establishing a Kindergarten Mothers’ Club, and finally the PTA president, who, after attending a conference in Trenton on infantile paralysis, proposed an annual March of Dimes dance on January 30— President Roosevelt’s birthday— that was accepted by most schools.

That one sentence is 142 words long, but it is not a run-on! In fact, extremely long sentences are not unheard of in English and American literature: one sentence runs 4,391 words in James Joyce’s Ulysses; another sentence has 13,955 words in Jonathan Coe’s novel The Rotters’ Club; and a sentence in Nigel Tomm’s The Blah Story reportedly has over two million words!

That one sentence is 142 words long, but it is not a run-on! In fact, extremely long sentences are not unheard of in English and American literature: one sentence runs 4,391 words in James Joyce’s Ulysses; another sentence has 13,955 words in Jonathan Coe’s novel The Rotters’ Club; and a sentence in Nigel Tomm’s The Blah Story reportedly has over two million words!

Conversely, a short sentence can be a run-on. Consider the sentence “Gene studied Roger slept.” It has two independent clauses (“Gene studied” and “Roger slept”) joined without proper punctuation, so it is a run-on.

Two variations of a sentence will illustrate the problem of run-ons:

Choosing a new computer is difficult I may give up and keep my old PC. (two independent clauses run together without proper punctuation)

Choosing a new computer is difficult, I may give up and keep my old PC. (a comma cannot join independent clauses; example of a comma splice)

Let’s look at the most common methods to fix run-ons using the same sentence from above:

- Add a comma between the clauses followed by an appropriate coordinating conjunction. Not just any coordinating conjunction will work. It must make sense within the context of the sentence. The conjunction comes after the comma. If the comma is already there, you add only a coordinating conjunction.

Choosing a new computer is difficult, so I may give up and keep my old PC.

- Separate them with a semicolon, which serves the same purpose as the comma + the conjunction. This solution works if two independent clauses are closely related. (If you are dealing with a comma splice, change the comma to a semicolon.)

Choosing a new computer is difficult; I may give up and keep my old PC.

- Add a period between the two independent clauses, or, in a comma splice, replace the comma that is already there with a period.

Choosing a new computer is difficult. I may give up and keep my old PC.

- Make one clause subordinate to the other. To do so, add a subordinating conjunction to the beginning. You may also need to add proper punctuation. In this example, a comma is needed after the subordinate clause that begins the sentence.

Because choosing a new computer is difficult, I may give up and keep my old PC.

If you have trouble with run-ons, you will probably admit that both carelessness—writing too quickly, not paying attention to punctuation, etc.—and a lack of knowledge about sentence structure contribute to errors in that area. Since you now know more about independent clauses, a careful examination of your writing will reveal run-ons and let you fix them.

To check your understanding of run-on sentences, do the brief interactive exercise.

Learning Some Tips and Tricks

- Check several sentences in one of your essays to see if you're using the same sentence structure over and over again. If you are, make it a point to vary your writing with different kinds of sentences now and then. As a reminder, there are four kinds of sentences: simple, compound, complex, and compound-complex.

Simple sentence = one independent clause and no subordinate clauses (IC)

Great literature stirs the imagination.Compound sentence = two or more independent clauses but no subordinate clauses (IC + IC)

Great literature stirs the imagination, and it challenges the intellect.Complex sentence = one independent clause and one or more subordinate clauses (IC + SC)

Great literature, which stirs the imagination, also challenges the intellect.Compound-complex sentence = two or more independent clauses and one or more subordinate clauses (IC + IC + SC)

Great literature, which challenges the intellect,is sometimes difficult, but it is also rewarding.

- In addition to varying the kinds of sentences you use, vary the length of those sentences. You don’t need to write long sentences unless you’re comfortable doing that. In fact, inserting a short sentence for emphasis is an effective technique. Here’s an example of varying sentence lengths for effect:

Knowing that reading would put her to sleep no matter how good the story was, Rita yawned, stretched, and reached for the thick novel on her nightstand. Just then, she thought she heard a noise. Barely allowing herself to breathe, she slowly sat up and put on her robe. Then the doorknob began to turn. She froze.

- Don’t forget to edit for parallel construction. (See lesson on coherence and transitions for more information on parallelism.)

- Reading your compositions aloud, so that your ears as well as your eyes can detect completeness, will help you find sentence-structure errors, especially run-ons. You might also find awkward sentences by reading aloud. If a sentence requires a second reading to be clear, it may need to be rewritten.

- Don’t be surprised if you sometimes find fragments and run-ons in even the best newspapers and magazines. Professional writers may manipulate sentence structure any way they want, but that autonomy is for the professionals. Stick to the accepted conventions of formal writing while you are sharpening your skills as a writer and editor. (Generally, the rules for creative writing are different, but that topic is, as the saying goes, “another can of worms.”)

Your Turn

Copy and paste the following paragraph into your Take Notes Tool and read it carefully. If a sentence is a fragment, highlight it in yellow; if it is a run-on, highlight it in purple; and if it is a correct sentence, do nothing to it. When you are finished, check your understanding.

I have never known anyone who was a better worker than Paula. Who always did her homework in half the time I took. Concentration was the secret of her success, she undoubtedly had a keen mind. I asked Paula to help me with my math once when I was particularly desperate. She could do the problems easily, and she could explain them to me. So that I could understand them. Mr. Jones, who was my math teacher, was very surprised when I knew how to do the problems. Without asking any questions. He was proud of me, I was proud of myself. Proved to be a turning point in my math education. From then until the time I graduated, I never made a math grade lower than a B. Paula never knew it her helping me with my homework eventually led to my career in engineering. I am successful today, someone took the time to help me when I needed it. I will never forget the smart girl who changed my life. Paula, the hard worker.

I have never known anyone who was a better worker than Paula. Who always did her homework in half the time I took (1). Concentration was the secret of her success, she undoubtedly had a keen mind (2). I asked Paula to help me with my math once when I was particularly desperate. She could do the problems easily, and she could explain them to me. So that I could understand them (3). Mr. Jones, who was my math teacher, was very surprised when I knew how to do the problems. Without asking any questions (4). He was proud of me, I was proud of myself (5). Proved to be a turning point in my math education (6). From then until the time I graduated, I never made a math grade lower than a B. Paula never knew it her helping me with my homework eventually led to my career in engineering (7). I am successful today, someone took the time to help me when I needed it (8). I will never forget the smart girl who changed my life. Paula, the hard worker (9).

- Fragment; subordinate clause beginning with relative pronoun who

- Run-on; two independent clauses joined by a comma (comma splice)

- Fragment; subordinate clause begins with subordinating conjunction so that

- Fragment; phrase

- Run-on; two independent clauses joined by a comma (comma splice)

- Fragment; phrase

- Run-on; two independent clauses run together

- Run-on; two independent clauses joined by a comma (comma splice)

- Fragment; phrase

Close

Resources

Resources Used in This Lesson: Bibliography

Fowler, H. Ramsey, and Jane E. Aaron. The Little, Brown Handbook. 10th ed. New York: Pearson Education, 2007.

“Grammar Tutorials – Sentence Structure: Correcting run-ons and comma splices.” John Jay College of Criminal Justice. City University of New York. http://resources.jjay.cuny.edu/erc/grammar/structure/ex6_n1fla.php.

Harris, Theodore L., and Richard E. Hodges, eds. The Literacy Dictionary: The Vocabulary of Reading and Writing. Newark, DE: International Reading Assn., 2005.

“Nigel Tomm Publishes the Longest Sentence Which Contains the Longest Word.” PR Leap (blog). http://www.prleap.com/pr/121058/.

Rickard, Diana. “A very long sentence.” CAC.OPHONY (weblog). June 27, 2008.

http://cac.ophony.org/2008/06/27/a-very-long-sentence/.

Warriner, John E., and Francis Griffith. English Grammar and Composition: Complete Course. Dallas: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1977.